On the 25th Anniversary of the Publication of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest

Original text: Patricia Nitzsche

Translation: Michelle Standley, PhD

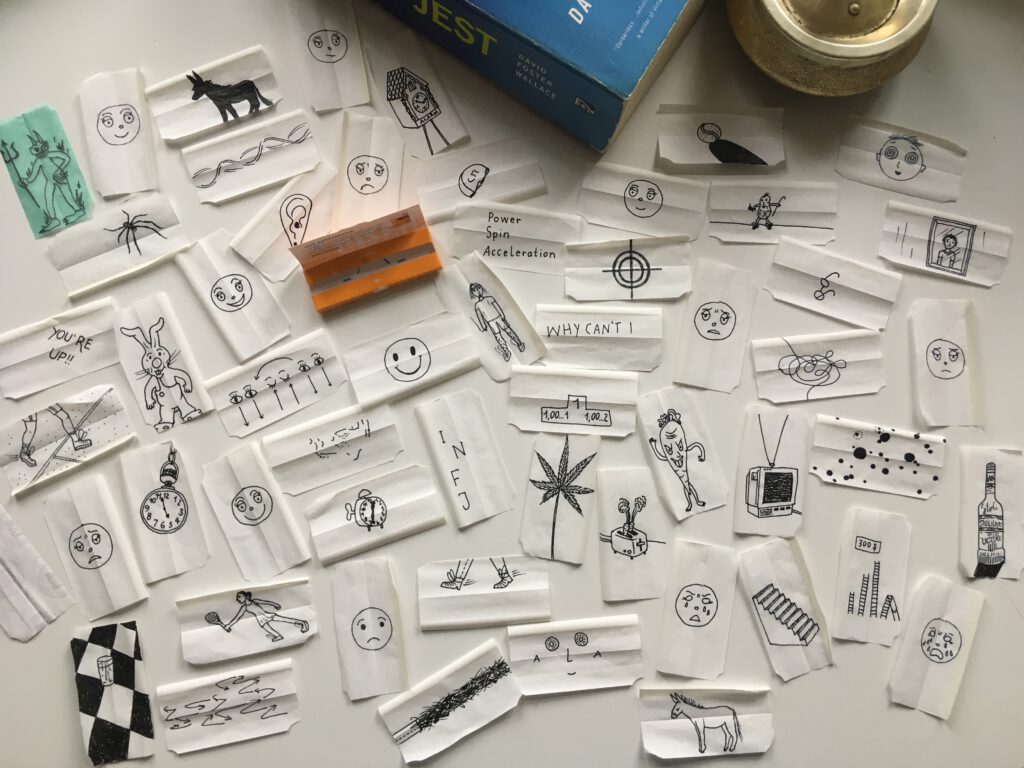

Illustrations: Maika Hassan-Beik

Everyone mentions Orwell’s 1984, whenever the topic comes up about which fictional dystopia best applies to our current situation. But I think there’s a more suitable candidate: Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace. The pandemic has made it particularly relevant to our times, but that’s not the only reason why it’s the most relevant novel right now. So, what’s going on here in Infinite Jest? We’ve got a society that spends all of its time in front of the TV and that is under threat from a sort of media virus. We’ve also got a pretty ludicrous, nihilistic separatist group that wants to use this very “virus” to combat the system. There’s also a community with coercive tactics whose privileged members are only able to endure the grinding, repetitive nature of their daily lives with the aid of a great deal of discipline and a small dose of drugs. There’s another, more dicey, community with similarly coercive tactics, whose members consist of high-risk patients who waggle their way from one day to the next, encouraging each other in self-help groups with names like “Tough Shit You Still Can’t Drink” (substitute “drink” with any pandemic restriction). Hanging over everything is the omnipresent awe and fear of the outside world, the “Out There,” that is both an attraction and a threat. These similarities aside, Infinite Jest is, at the very least, simply an incredibly big book with which you could kill an incredible amount of time at home. Think about it: another lockdown is surely on its way!

The truth is, this essay is not so much about pandemics or other social catastrophes as it is about black holes and the infinite spaces between zeroes and ones. And a little about carrots too.

– I –

Today is Sunday, November 8th, Interdependence Day. I’m sitting on my bed. I’ve just slammed the “big book” shut that I’ve spent most of the year reading. I’m going over in my head what I’ve seen, heard, and felt during my second go ‘round of infinite jesting.

I’ve discovered that drug addicts who turn to crime to finance their addictions are rarely involved in violent crime.

I’ve discovered where 90 percent of the American upper classes stash their safes and their silverware.

I’ve found out that Canadians lift a leg when they fart; that Germans lower their voices when they want to make a strong impression or appear threatening; that kids who come from the lower classes put their shirts on head first, then arms, instead of the other way around; and that they put on their shoes and socks in the following order: sock, shoe, sock, shoe.

I’ve learned about how I, as a reader, automatically imagine the physiognomy of the characters as basically “normal.” Infinite Jest will disabuse you of that idea pretty quickly, though. Apart from all of the farting, sweating, and vomiting, the novel practically teems with abnormalities and deformities, some of which are so bizarre that they’re almost believable.

I’ve also looked into the psychoanalytic interpretation of recurring nightmares in which teeth either fall out or break. I’ve had less luck in finding out about how to interpret nightmares in which faces appear in the ground, ceilings breath, or clock hands are frozen at 6:30 p.m.

I’ve learned a lot more about possible mental disorders and nervous tics, not to mention the range of possible chemical-pharmaceutical combinations and their effects.

I’ve started to count the various characters—even those mentioned only once—who have one-syllable last names. Total number: 85 (if you count the cojoined twins Caryn and Sharyn Vaughn as two people).

I’ve been told that gifted bureaucrats tend to be physically small, and that you can make pretty good poached eggs in the microwave.

I’ve asked myself how much would possibly remain of a head after someone who wanted to commit suicide had put it in a microwave that they had outfitted for just such a purpose. This was then followed by the question of whether this method would be preferable to suicide by garbage disposal.

I’ve got to admit, after reading some passages I had images in my head that I wish I’d never had. In reading other passages, though, I’ve experienced a sort of ecstasy, which I’ve only otherwise known during concerts—this surely has something to do with DFW’s incredible mastery of tempo and rhythm.

I’ve learned that Raquel Welch’s face and Linda McCartney’s voice (and to a lesser extent, Winston Churchills’ head) can inspire horror.

I’ve tried to keep track of all the references to Shakespeare’s Hamlet (and read Hamlet for the first time). Answer: a few.

And without any real evidence to prove it, I’ve become convinced that there’s a secret message hidden behind the novel’s first two words and the very last one.

If this introduction strikes you as somehow familiar, that’s probably because you’ve encountered some other works from David Foster Wallace (DFW), most likely the essay “A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again” (ASUPFTH). At the beginning of the essay DFW follows a similar format, summarizing in list form observations that he gathered during a week onboard a luxury cruise ship. According to a very informal survey that I conducted, ASUPFTH is DFW’s most well-known work. But that’s not the sole reason why I decided to open the discussion of Infinite Jest (INFJ) with this text. There’s a lot more connecting the two works than may be obvious at first glance. You might be surprised that an account of an all-expenses paid week on a luxury liner and a book with a title like Infinite Jest share a profoundly melancholy undercurrent (which does not, however, mean that they are short on fun). You could even say that the cruise ship essay prepares the way for what DFW will deal with in more depth in Infinite Jest, which was published not long after ASUPFTH. Both consider “death/despair/pampering/insatiability issues” (ASUPFTH, 821). In both, DFW seeks to answer the question: Why are we drawn to being amused (pampered/entertained) to death?

After ASUPFTH, there’s another essay by DFW that a lot of people are familiar with, This is Water (TISWA). The work actually comes from a speech that DFW gave at a college graduation three years before his death. It was posthumously published as a book. If you’re in need of a gift that borders somewhere between the personal and impersonal, the slim volume is perfectly suited for pulling off the shelf from your local bookstore’s “Popular Philosophy” section. With it in tow, you could show up to a birthday party and quite nonchalantly impress your hosts with your distinguished taste and remarkable depth. You can’t go too far from wrong attaching yourself to DFW’s evident brilliance. Be forewarned, however, that there’s the risk that when viewed out of the context of DFW’s larger body of work, TISWA may come off as a bit kitschy, somewhat in the style of self-help literature, which would be a real injustice to DFW. To silence such criticisms from people who think that DFW traffics in such conventional morality, I’d like to wave under their noses the fish tale that lends the essay its title. I’m referring to a rather tasteless, sexist joke that has to do with the smell of fish. It’s told after an Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) meeting by someone named Robert F., a.k.a. Bob Death, who apart from being sober embodies every other cliché related to macho biker types.

I’m bringing up TISWA before getting into Infinte Jest because, like ASUPFTH, it has a great deal in common with Infinite Jest. TISWA does in a very condensed form what Infinite Jest does in a more subtle and literary one. Both examine our perception and how we grapple with our everyday existence, themes, which are, well: incredibly unsexy.

– II –

A word to the wise: If you plan on reading Infinite Jest like a regular novel with a linear structure, you’re going to be disappointed at first by this over 2-lb brick. The plot is the absolute opposite of linear: It skips around in space, time, characters, and in style and narrative; with its countless cross references, made even more challenging by its nearly 400 footnotes, some of which even have their own footnotes, its practically incomprehensible. And, yeah, I’m sorry, but you really should read the whole thing, all of it. Welcome to the “Tough Shit You Still Can’t Skip” self-help group.

Just as it’s difficult to readily identify a plot in Infinte Jest, it’s equally challenging trying to assign it to any obvious genre: meta-/post-/post-post-modernism? Check. Social satire? Double check. Tragi-comedy? Absolutely. Encyclopedic novel? That it is. “Hysterical realism”? No idea what exactly Wikipedia meant by that, but it sounds right. You could go on like this for hours and still not account for them all. Parallels with the classical tragedy Hamlet have already been noted, but I haven’t yet mentioned the even stronger connection to the classical comedy sketch from Monty Python, The Funniest Joke in the World. Then there’s parallels with Alfred Hitchcock. The film circulating in Infinite Jest, with the presumed title Infinite Jest functions like a typical Hitchcockian “MacGuffin.” When reading INFJ, such 1990s pop-cultural classics from The Big Lebowski to Pulp Fiction and Trainspotting also come to mind. It’s even got such standard fantasy elements as objects, gurus, and ghosts that hover and float in mid-air. An obvious theme still missing from this list is the genre of utopian or rather dystopian literature. Based on the book’s date of publication in 1996—in Infinite Jest it’s the “Year of the Depend Adult Undergarment” (Y.D.A.U.)—the story takes place ten years after the Infinite Jest was published.

Happiness Is a Warm Gun

Bear with me here. I’m going to venture a hopelessly inadequate attempt to unravel the plot of Infinite Jest. The US has united with Canada and Mexico to form an organization called O.N.A.N. Its president is Johnny Gentle, who used to be a crooner and who is, to put it kindly, “not exactly the most candent star in the intellectual Orion.” In the absence of any real external enemies, O.N.A.N. has turned its attention to cleaning up its own members’ countries, quite literally. Gentle’s Clean Party is committed to “annular fusion,” a complex process of waste disposal that is so efficient that it also eliminates all possibilities for sustaining life on the surrounding territories (in Québec or thereabouts). The Clean Party also focuses its attention on combatting Canadian separatist groups, such as the “Assassins des Fauteuils Rollents” (A.F.R.), who are willing to go to any extreme to get Québec to secede from O.N.A.N. Weapon of choice is a film whose content is apparently so enthralling that the viewer is unable to turn away. The only thing they can do is sit on their butts and watch, their eyes spinning in rotating spirals. (Rumor has it that those affected die with a smile on their lips.) The film, called “the samizdat” by insiders, has already claimed its first victims. In addition to the A.F.R., the US Secret Service are also interested in getting ahold of the film’s master copy. It’s not revealed where the master copy is nor what its exact content is, but there are hints that it’s likely hidden in Boston in one of the novel’s two main locations. One is the “Enfield Tennis Academy” (E.T.A.), with 17-year-old Harold (“Hal”) Incandenza. Hal’s the youngest son of an annular fusion pioneer, James O. Incandenza, founder of the E.T.A. and alleged creator of “the samizdat,” who committed suicide four or five years prior. Hal has encyclopedic knowledge and is a talented tennis player with good prospects for the “show,” i.e., success and fame in the professional sport. Only a few people know that Hal smokes pot and even fewer suspect that it has something to do with the incredibly deep emotional emptiness that he’s felt since childhood. The master copy of the film may also be with Donald (“Don”) Gately, a former poly-drug addict and criminal who is now a member of the staff at Ennet House Drug and Recovery House. He’s racking his giant, square head over how to find his own God and over how to figure out if the clichéd mottos spouted off by AA veterans might actually be true.

– III –

Before we turn to the actual main plotline, let’s briefly return to the question of genre: There’s every reason to believe that fans of classic science fiction would definitely get their money’s worth from Infinite Jest. It’s set in the (near) future and this future has got some intriguing technological innovations. It’s got annular fusion with side effects of nearly apocalyptic proportions. And it also weaves into the plot new types of communication and entertainment media.

Nihilistic Binge Watching

Videotelephony didn’t catch on in the Y.D.A.U.’s Boston branch, the reasons for which are described in detail (let’s say it’s got something to do with “hysterical vanity paranoia”). Cable television, by contrast, has long since been replaced by a new type of digital technology that’s more or less synonymous with the “InterLace TelEntertainment” company. The secret of its success lies in its ability to rouse the notoriously bored viewer from their passive state and guarantee them “[t]otal freedom, privacy, choice” (INFJ: 620) in their selection of programs. Digital networking has been a part of the standard infrastructure for a long time:

“Half of all metro Bostonians now work at home via some digital link. 50% of all public education disseminated through accredited encoded pulses, absorb-ableat home on couches. […] One-third of those 50% of metro Bostonians who still leave home to work could work at home if they wished. And (get this) 94% of all O. N.A.N.ite paid entertainment now absorbed at home: pulses, storage cartridges, displays, domestic decor – an entertainment-market of sofas and eyes. […] But so very much private watching of customized screens behind drawn curtains in the dreamy familiarity of home. A floating no- space world of personal spectation.” (Ibid.)

That’s a fairly apt description of what our everyday lives are like today, one quarter of a century after Infinite Jest was published. The only difference is that “TV” is no longer just a rectangular piece of furniture or a display that we stare at from our sofas. It’s a mobile device that we can pull out of our pockets at any time and any place, transforming our space into a living room, office, gym, classroom, etc. The ease with which we can do this encourages us to think (or suggests as much) that we have unlimited choices. This is a phenomenon that also describes how we may be irresistibly attracted to something. There’s another term you could use to describe this: dependency. And dependency, in its most extreme form, addiction, plays a central and multifaceted role in Infinite Jest.

Let’s stick with digital networking for a moment. Like pretty much all technology-based social innovations that came before, we no longer see the digital revolution as the ultimate solution to every sort of social problem. When we talk about it, we usually focus on its darker side and the new social problems it’s created. We’ve come to realize that the Internet is not only a medium that facilitates the rapid dissemination of information to the farthest corners of the planet, but that it’s also one particularly well suited to distorting or manipulating information. We’ve come to recognize that it promotes networking and communication on a global scale, while at the same time creates dangerous filter bubbles and echo chambers. We’ve come to appreciate the fact that the Internet provides access to an incredible diversity of art, culture, and entertainment—in short, to creativity in its various forms—something that would have been unthinkable in the pre-Internet age. In addition to all these insights, we’ve also figured out that the Internet brings with it a new type of dependency.

The Corona pandemic has made our dependency on a stable Internet connection all the more apparent, while at the same time it has intensified that very dependency. We can’t hardly do anything anymore with the Internet in its mobile, high-speed variant; it’s as much a part of our physical and mental infrastructure as traffic or health care. Even under normal conditions, a collapse of the main servers would be tantamount to a nuclear meltdown. It’s hard to imagine what would happen in an exceptional situation like a national lockdown.

This reveals how bound up dependency is with vulnerability. And that further suggests how easily our dependence on the ultimate communication-and-entertainment medium could very easily be used against us, as a terrorist weapon.

In Infinite Jest, “the samizdat” represents just such a weapon. It targets US (or Western, postmodern) society’s allegedly most vulnerable spot: its obsessive desire for—or addiction to—entertainment. “The samizdat” seizes on this craving and takes it to a deadly extreme. Entertainment is so entertaining that it wholly absorbs a person’s attention. It then gradually kills off all other human needs, to the point where the entire organism falls apart. “Fun” becomes “Too Much Fun.”

To understand the role that “Fun” plays in Infinite jest, it’s got to be appreciated within the context of DFW’s larger body of work. If you get to know it a little better, you’ll quickly realize that his protagonists rarely use their preferred drug (whether that’s entertainment or crack) because they’re seeking to intensify a positive sensation. It’s more likely that they are turning to a drug of some sort to forget or to at least make bearable negative sensations, such as their perceived inadequacy, emptiness, boredom, or complete despair. They don’t get drunk at a party to have more fun. They do it so that they can present themselves to other party guests as more attractive, more self-confident, or wittier than they really are (or than they think they are) when they’re sober. They don’t sit in front of the TV for hours to watch people going about their daily lives in a way that resembles their own; they want to identify with people who lead lives that are a lot more exciting than theirs. And if they book a trip on an incredible cruise ship it’s not because they believe that this one week of “managed fun” (ASUPFTH: 817f.) will surpass the rest of the year in terms of its feel-good factor. They do it because they hope the prospect of it will help them get through their exhausting, if not completely detested, workday or everyday life. In short, the addiction to entertainment or fun is an addiction to distraction/diversion/sedation.

With this in mind, we can now delineate the crucial difference between the fictional “samizdat” and real streaming services: (1) Lethal, addictive, passive-entertainment that completely satisfies the viewers’ desires doesn’t yield any profits for its producers. In this respect, the A.F.R. separatists who pedal “the samizdat” are like drug dealers who sell a lethal overdose to a first-time buyer. Not an exactly busines-savvy approach. Compare this to mobile, high-speed Internet. It’s so effective and so appealing because it’s so good at supplying its users with new(er) substances for as long as possible. It thus does more than merely keep the addiction alive, it deepens it. Put differently, the Internet expands and differentiates its users’ range of needs; it doesn’t try to satisfy them completely. (2) The sort of passive entertainment offered by “the samizdat” seems a bit antiquated by today’s standards. Even within Infinite Jest, the development of InterLace underscores the idea that sooner or later passive entertainment will reach the limits of its power to engage consumers. It doesn’t matter how many choices are on offer (how many movies, TV series, etc. are put out on the market every year). Your typical binge watcher will, at some point, find everything repetitive, in some way or another. Infinite Jest doesn’t bring this insight to its obvious conclusion. Even with InterLace, the consumer remains passive; their activity doesn’t go far beyond placing their thumb on the on-off switch on the remote control. Infinite Jest is primarily concerned with Generation X and its offshoots, which are still used to consuming anything that’s served up. Millennials and their successors, by contrast, grew tired of such passive consumption a long time ago.

“The samizdat” is, as discussed above, thus meant to satisfy people’s general need for escape from the everyday, a need that it over-satisfies. This form of entertainment addiction is about people confronting their inner black holes, and about silencing, at least briefly, the voice that is constantly whispering in their ears, the one that tells them that existence is essentially meaningless. Infinite Jest remains focused primarily on passive entertainment, which in strictly economic terms is an unnecessary constraint. Writing eight years before the founding of the first social media platform, DFW underestimated—at least in terms of the philosophy of technology—the enormous (addictive) potential that’s inherent to another need: recognition. Why should you limit yourself to viewing what’s being featured right then, as selected by the corporate media, when you could instead turn to social media and feature yourself, around-the-clock? Why should you hold back on experiencing your own meaninglessness when you’ve got the chance to counter it by experiencing something meaningful? (What you do on social media must have some sort of meaning. If it didn’t, no one would respond to it, would they? Would they?!?!)

There’s a lot of evidence to suggest that mobile, high-speed Internet could be developed into the ultimate-attention-absorbing drug for the very reason that it fulfills this need for passive distraction/diversion/sedation and that it, at the very least (!), fulfills the need to-be-seen, that is, for acknowledgement/recognition/affirmation. Not long after the emergence of “digital show business 2.0,” a.k.a. social media, consumers became producers, busy delivering new content every second. To help them, there’s a broad range of options: On Twitter, for instance, you can toggle between participating in a discussion about the most sustainable and foamable milk alternative on one thread, while trying to incite members of your Kittylove WhatsApp group to fantasize about how to torture alleged cat abusers on another.

Mobile, high-speed Internet has somehow managed to seep into every pore of our private and public lives and to endlessly generate new needs. More followers! More like/clicks/comments! More attention! This puts it on par with capitalism, which for decades has succeeded rather well in planting its flag on every unmarked territory, i.e., on every non-commercial space that remains on the world map.

A Brief Digression on the Hideous “A-Word”

Let’s put things in a historical context: Infinite Jest came out in the mid-1990s when big-brand corporations were at their peak. No long after its publication, Canadian journalist and activist Naomi Klein examined their role in contemporary society in her groundbreaking book, No Logo. This marked the beginning of a phase of capitalism in which brand-driven corporations were no longer trying to sell merely their product but an entire lifestyle. As part of this new advertising strategy, they ceased to address consumers as a large, anonymous mass; they addressed them instead as individuals with individualistic needs who could potentially identify as closely as possible with the brand’s message. This phase of capitalism established the foundation for what seems almost self-evident today: Advertising and consumption are omnipresent, a 24/7 background noise, part of what could be called “the collective-mental default setting” (for more on this, see Section IV below).

In Infinite Jest, this total commercialization of life is represented by the corporate-sponsored years. The “Year of the Depend Adult Undergarment,” for instance, was preceded by the “Year of the Whopper” or the “Year of Yushityu 2007 Mimetic-Resolution-Cartridge-View-Motherboard-Easy-To-Install-Upgrade For Infernatron/InterLace TP Systems For Home, Office Or Mobile (sic)” (sic). If you compare it with today’s social media, it almost seems cute or naïve, because it’s so very obvious and tangible. YouTube & Co. have finally made the advertising industry’s long-cherished dream come true: They make advertising as individualized and as undetectable as possible.

In this pursuit, advertisers prize “ordinary” people whose promotional work is distinguished by a certain quality, not glamor or stardom, but authenticity. Stars don’t sell products as well as “completely normal people like you and me,” who “don’t pretend” and who only do something when they “really stand behind it wholeheartedly.” The more authentic or uncalculated their Insta-story recommendations come across—“you’ve absolutely got to try this-or-that-product;” #lifechangingexperience—the more followers and the more lucrative advertising contracts they’re able to secure. The more authentic or straightforward appears the path that led them to become who they are today—they were born to show others the way out of a life marked by self-hatred, shame, and ineptitude; #becomethebestpossibleself—the more money they’re able to earn with their life-coaching seminars.

This strategy of using supposed authenticity or “street credibility” to bolster sales is hardly new. Think of Che Guevara t-shirts, lumberjack flannels, or pre-distressed, holey jeans, all of which may have been hanging already on the racks of your favorite retail outlets in the year that Infinite Jest came out. In fact, capitalism’s dynamism and ability to adapt has always resided in its tension with authenticity. Within the capitalist ethos, a person is willing to sell themselves and engage in a permanent performance. The perceived authentic person, however, does not engage in self-presentation, follows their own principles, and acts without any sort of calculation. But it’s exactly this process of self-opposition from which capitalism benefits. It constantly creates islands of anti-commercialism that it can then conquer and transform to its own benefit. There’s another paradox, however, as it’s impossible to produce the authentic—that would contradict the perception that it’s something natural, unmediated. Yet, in the past few years, the attempt to convincingly produce the authentic has become an extremely lucrative market. As the thriving mindfulness/self-help/happiness industry is well aware, the postmodern individual devotes a great deal of time to uncovering their “inner core,” to finally “listening to their inner voice” and “living fully in the here and now.” And, if it turns out, that the uncovered core, voice, or moment doesn’t quite suit them then there are plenty of experts, ready with a host of methods, to help them find a way to derive some purpose from the whole pursuit.

Listening and Being Heard

In all of DFW’s works, appears the question of how much authenticity is possible in a totally commercialized, postmodern society. In his essays, he considers the consequences of maintaining a position of ironic distance, a position which is, if not created, then at least reinforced by advertising, hip sitcom characters, etc. As DFW sees it, such a position is the very opposite of sincerity and genuine empathy, in so far as it doesn’t require you to take any real risks. If you avoid confronting difficult realities, then you avoid confronting your own vulnerability. You merely comment on them from a safe distance. If someone criticizes you for something that you’ve expressed, you can defend yourself on the grounds that you only meant it ironically.

In DFW’s fiction, the protagonists are, in one way or another, either preoccupied with themselves or with the question of how they can convey a certain impression of themselves to their peers. They are, however, generally unaware that these same people are as preoccupied as they are with this very same question. This disconnection makes real communication impossible.

Communication is also an issue throughout Infinite Jest. The protagonists either attempt to speak but can’t manage to utter even a single word or the words themselves simply cannot break through to convey their real meaning to the intended audience. Sometimes the problem is that they literally don’t speak the same language, a source of misunderstanding with deadly consequences. Most of the time, though, the protagonists pretend to listen. There’s a variety of reasons for this—among their own internal and intellectual struggles—but the end result is that they’re unable to follow what’s being said. And it’s in exchanges like this, in which the protagonists talk past each other or even at the same time, that the novel unfolds. In DFW’s deft hands, such scenes can be amusing and even absurd, but they are never opportunities for subjecting their characters to ridicule.

Unlike a lot of authors of his generation, with DFW, it’s never about pure showmanship. If you really delve deeply into his works, you’ll quickly notice that he’s genuinely concerned about his protagonists and their development. Even the most minor character in Infinite Jest (and there are many of them!) has greater depth than most of the main characters in other novels, movies, or TV shows, that were then out. And this genuine concern—or let’s call it empathy—applies not only to the characters involved but also to the readers. You can’t deny that Infinite Jest can be unwieldy, overly complex, or simply long-winded. But you’d be doing DFW a real injustice were you to suggest that his main purpose is to show off his writing skills, with little regard for the reader’s patience. No matter how tiring it may be, every scene fulfills a consciously considered purpose. No matter how long-winded, every scene contains small, but nonetheless important, details. Throughout Infinite Jest, DFW spins webs with threads that he later picks up. And so the dialogues never run entirely into a void but only around a few bends until you end up at a completely different place than you would have thought possible when you started.

In addition to all of the issues related to communication, the protagonists also want desperately for people to hear and see them as they “really” are, i.e., without their having to pretend or perform. Take the Incandenzas: At the center is the mother, Avril, Canadian, agoraphobic and obsessive-compulsive and a kind of linguistic savant whose most obvious compulsion is probably her insistence on playing the role of the perfect “super mom.” She’s constantly subtly communicating to her children that she recognizes in them their individuality, loves them unconditionally, and supports them in whatever they pursue. This might all sound good, but everything she does comes across as if she’s memorized a parenting guide. Avril is also the widow of James O. Incandenza, who occupied a variety of roles over the course of his life: He used his expertise in optics both to co-develop the government’s annular fusion technology and to make his own avant-garde films; he founded and directed the Enfield Tennis Academy; and last, but not least, he struggled with serious issues related to alcoholism. James seemed quite capable of seeing behind the façade of his talented but completely emotional absent son, Hal. Yet, every attempt he made to get through to him was doomed to fail. Avril and James have three sons: The oldest, Orin, is a professional football player. Like many children of alcoholics and obsessive compulsives (or so we learn in Infinite Jest), he has a marked tendency toward hypersexuality, coupled with a distinct degree of self-centeredness. The youngest son, Hal, is an aspiring tennis ace, who inherited a talent for language from his mother’s side of the family. Hal doesn’t suffer from an overactive libido, but from pretty much the opposite, the absence of any inner emotion life at all, something called “anhedonia.” From a young age, he learned how to maintain an impenetrable façade, and he found the right tools to do so: foremost among them, “Bob Hope” or cannabis, which he smokes secretly every day in the E.T.A. basement. His performance appears to be in danger of being unmasked, however, when he’s forced to temporarily quit smoking pot in favor of a drug that is less easily detected in a urine analysis (DMZ). The result of which is that, as other people point out to him, he gradually loses control of his facial expressions and his ability to speak.

Mario, the middle son, doesn’t fit the family pattern. He was born with a physical deformity and can only move upright with the help of an adjustable police lock. His almost childlike sincerity makes you think that he’s also mentally disabled, but this would be a real underestimation of Mario’s abilities. He’s talented with a camera and continues to produce his own films after his father dies; and he’s one of the few protagonists—and the only one in the Incandenza cosmos—who understands the things and people that surround him. This perceptiveness includes picking up on the deep-seeded sadness of his brother, Hal, with whom he shares a room at E.T.A. and whom he genuinely loves. Because Mario doesn’t have the same ambition that drives the tennis kids and all the other “normal” people around him, i.e., those who don’t have a physical handicap, he doesn’t feel the same pressure to perform. People are drawn to Mario. This is presumably because they sense that in his presence, they don’t have something to prove or to perform.

When struggling with insomnia, Mario sometimes spends time at the nearby Ennet House Drug and Recovery House, where among its freakish residents, he doesn’t stand out. The residents there, he observes, lack the sad aura that he observes at E.T.A. This is probably because at Ennet House they’re not in competition with each other for a reward for best performance. Most of them are more preoccupied, initially at least, with their own survival. They are so absorbed with meeting their basic physical and psychological needs that they worry about everything but the issue of what sort of impression they are making on other people. And if, during the evening AA meetings someone does get it in their head to spice up their own story of decline with some self-ironic commentary that might illicit some empathy, the group doesn’t hesitate to put them in their place. At AA meetings, it’s got to be the truth and nothing but the truth.

At the center of the Ennet House cosmos is Donald (“Don”) Gately. Like most of his fellow sufferers, when still in the throes of addiction, he devoted all of his energy to getting his hands on the next dose (in this case an opioid, the powerful painkiller Demerol®). Since then, he uses those same reserves of energy to internalize mottos or mantras about endurance passed along by AA sponsors and on searching for something else to fill the inner black hole that the drug had masked. At one of the evening AA meetings, Gately realizes that for the very first time in his life, he’s able to really listen to someone else as they stand before the group and give an honest account of their descent, of their break downs in their families, society, and health that eventually forced them to stare into the existential abyss. For the first time in his life, Gately asks honest questions of himself and others. In the course of the plot, he even finds the strength to confront his demons in the form of flashback-like nightmares.

This brief overview is meant to illustrate that in Infinite Jest authenticity is always negotiated as part of experiencing something physical, even pain and suffering, and not as part of wanting to please someone else. Authentic moments and authentic communication, it suggests, only take place when the protagonists are forced to contend with themselves and their own naked vulnerability in some form or another. This runs contrary to the conceit behind social media—and not only if you look at the all-too-beautiful picture galleries on Instagram or what are probably sponsored image campaigns behind things like #bodypositvitiy. Social media is meant to represent mediation. The person on one side of the screen can only ever view what the person on the other side of the screen understands and/or wants to convey as their authentic self. Some sort of filter, or another form of control, is always present, even if you, as an influencer, mean it when you apply the #nofilter hashtag and don’t merely see the depiction of flaws and non-perfection as part of making your image more marketable, more uniquely saleable. The body, or physical experience, is not relevant here, cannot be; it’s always reproduced in a mediated form.

Put differently, the people on the two sides of the screen are never quite inhabiting the same moment. Keep this thought in mind when you read the section below.

– IV –

To bring the question of genre to a close, for the time being at any rate, fans of dystopian/sci-fi literature would probably not name Infinite Jest as one of their favorite books. If you consider that dystopian/sci-fi literature is largely concerned with examining how individual behavior and social relationships change when the social default setting changes or has already changed, then Infinite Jest has a fundamentally different angle. In Infinite Jest, the world outside remains on the borders, appearing only symbolically as a potential threat. The protagonists don’t fear the outside world because of annular fusion’s potential post-apocalyptic consequences or the deadly “samizdat”; they fear it because it holds very real temptations and difficult choices the sorts of which plague the postmodern individual, not in the future, but in the present.

The aspiring tennis pros at E.T.A. see the outside world as synonymous with “the Show,” i.e., the appearance on the international tennis stage that promises fame, recognition, or even redemption. The coaches know all too well that exposure to such adulation and pressure may inspire their players to lose touch with reality altogether. The coaches thus try to isolate them from the outside world for as long as possible and to condition them in the arduous daily training sessions with the message that nothing else matters but hitting the little yellow ball in front of them.

The residents of the Ennet House clinic, by contrast, see the outside world as the “Out There,” primarily linked to the danger of a relapse into addiction and their old destructive habits. They thus try to isolate themselves from outside influences for as long as possible. Regardless of how stable they feel, they cling to the mantras espoused by their AA sponsors, which essentially consist of adhering to the, sometimes tiring, daily routine of AA meetings—no matter what.

The main protagonists in Infinite Jest move within their own microcosms, which in turn remain relatively unaffected by the social or even political influences around them. In contrast to classic dystopian or sci-fi literature, Infinite jest is less concerned with social default settings and group dynamics than with purely individual default settings which cannot be completely separated from these, but which are nevertheless adjusted differently, according to the individual.

Infinite Spaces

Here I’d like to introduce the term “default setting” (D.S.), a term borrowed from computer science, to discuss the “0-1 structure,” which is the basis of computer programing. In layman’s terms, the default setting means the “standard setting,” i.e., the state that is initially present (0) before anything in it is changed (1). If you apply this logic to society, then the D.S. forms the frame of reference against which society orients itself, that is, the combination of all that the majority defines as legitimate or the norm. This societal norm is, of course, immensely complex; the total 0 is composed of a multitude of zeros in different domains. Moreover, it is by no means static, such that it might be preferable to speak in the mathematical sense of a permanent “approximation to 0” or of the “lowest common denominator” on which the majority of the members of society can somehow agree at any given historical moment. Despite all of these relativizations, certain general statements can nonetheless be made about the current zero or norm, such as “we live in a democracy,”; “innocent until proven guilty”; “minorities are protected by the law”; “no pain no gain”; or “time is money,” etc.

Since our brain is wired to perceive only differences, we’re usually unaware of what constitutes the “normal” state. Like the fish discussed above, most of the time we don’t have even the foggiest idea of what water actually is. We only notice the normal state when we make comparisons or when the state has changed fundamentally, i.e., the 0 has turned to 1. This becomes especially evident when there are sudden changes brought on by external events such as natural disasters, terrorist attacks, nuclear reactor explosions, or even pandemics. They require a quick reaction and adaptation. Then the peculiar side effect emerges that what used to constitute the normal state of affairs, and was thus invisible, suddenly becomes visible. And all at once it’s difficult to imagine how we used to carry out our daily lives, without the adaptations that we’d quickly made in the aftermath of the event that transformed them in the first place. The old 0 has turned into a 1, which in the course of time asserts itself as the new 0, until again something fundamental changes in the current state and the new 0 becomes the newer 1.

This shift to a new state can, however, and does, occur just as gradually and it does so more frequently; as part of the various intra-societal negotiations, they ensure that society as a whole continues to develop in a certain direction. Again, here we are closer to mathematics than to computer science. What’s not represented in the binary 0-1 logic is the mathematical fact that between the 0 and the 1 there is an infinite intermediate space of fractional-rational numbers. Even if it can be proved mathematically—which is the case—that 0.99 period is equal to 1, the 0.99…9 in some space-time continuum once followed the 0.99…8 and this 0.99…8 is not yet equal to 1—not to mention the 0.98… and so forth. Transferring the concept to the context of society, it’s nevertheless possible to identify the new 1 in contrast to the conventional 0 (comma-something) by means of comparisons. This can be effectively demonstrated by the example of what’s considered permissible to say in public: Today public pressure can lead the dismissal of a corporate executive for making a racist or misogynist statement, something that would have been unthinkable a decade or two ago, when the public’s response wouldn’t have moved far past a mere expression of their disapproval with it. The 0 = “Can be said in public without consequence” has become a 1 = “You should think twice before saying it in public and, if you’re not sure, you will have to reckon with possible contradictions and consequences.”

Whether sudden or gradual, changes in the society’s D.S., or frame of reference, are always accompanied by changes in the expectations and demands that its members legitimately place on it. In modern, affluent societies, these demands and expectations (reference points, for short) go far beyond the satisfaction of basic needs, and they continue to shift as the D.S. changes. However, since we usually don’t notice this movement due to our neurological D.S., this can have paradoxical effects. A prime example of this is the acceleration of certain phenomena within society: The technological innovations of the last 100-something years have made it possible for more and more members of the most affluent countries to work less, a change which should have opened up greater reserves of time. But the exact opposite has taken place. Instead, the more privileged members of such societies have less and less time at their disposal. The reason for this is because society’s baseline reference point is no longer attached to the stagecoach but to the 5G network. Its members’ demands and expectations have grown accordingly. Thus, an activity that used to take a good part of the day, now has to be completed within one minute. “What goes around comes around”—a fitting description of the newly “available” reserves of time.

The unconscious shift in reference points can have a similarly dangerous effect. This is because the shift away from a fixed quantity, a base, leads to the formation of bubbles that at some point burst—in some cases with devastating consequences for society. Take economic bubbles, for example. Social aspirations and expectations rest on steady economic growth. But over time this growth is generated less by the creation of value in the real economy and more by debt and the production of virtual money; a spiral cycle then develops in which the logic of the financial markets becomes increasingly detached from the “real economy.” This cycle continues until something disrupts one of these elements and leads to the collapse of the whole artificial construct. The banks can no longer issue money; borrowers can longer service their loans; and, finally, the state has to step in. Or consider the virtual filter bubbles (echo chambers, rabbit holes, etc.). They are created when users first look for virtual platforms on the Internet where they find recognition and affirmation for their assumptions. Algorithms continue to supply users with content that reproduces their assumptions and steers them a little further in a particular direction, such that these echo chambers of affirmation increasingly drown out other sources of information, until such sources disappear altogether. In keeping with its social aspects, social media introduces users to others who share similar views. By creating opportunities for a direct exchange between the likeminded, social media thus facilitates the gradual creation of a radicalized worldview that is decoupled from mainstream society. Most members of society don’t notice that this is taking place until supporters of conspiracy theories take their slogans out of the virtual world and onto the streets, or until an individual feels so bolstered by their virtual community that they translate their virtual, verbal violence into a literal, physical one.

Only when the economy collapses and private households are in dire straits, or when assassinations and murder attempts are carried out with an openly political or religious motivation does the public finally notice this shift of violence from the virtual to the physical world. Only then are they forced to try to reconstruct the various forces that turned the 0.99…8 into a 1. Only then do they break out in a panic and express their horror, setting lofty goals, and vowing to prevent something like this from ever happening again. However, as we know all too well from our own experience—and have to be reminded of again at least once a year—it’s one thing to make good resolutions, it’s another to follow through on them.

Half-Empty and Half-Full Glasses

This brings us to the individual default settings. You could say that this is about the “standard equipment” with which an individual comes into the world or about the frame of reference within which an individual’s demands and expectations of life (their own reference points) are formed. Both are embedded in society’s D.S. and further adapted by social and purely individual (personality) traits. For example, a child who is raised in late-20th-century US by someone who is either unemployed or an addict who has a series of violent partners (see Don Gately) will almost certainly have different demands and expectations of life than a child born into a US upper-class family that is perhaps equally addicted to some sort of substance but academically inclined and fosters their children’s talents (see Hal Incandenza). And this upper-middle-class family’s other son, born with a serious physical deformity, probably has different demands and expectations from life than his brother, who was not born with such a physical deformity. Nevertheless, it’s just as possible for the more privileged child to develop into a depressed adult as it is for a less privileged child to move through life relatively content or to establish a career.

If they start from the base of this individual standard equipment or within this individual frame of reference, shifts in which the normal state 0 changes into a new state 1 are constantly taking place.

Such shifts can also happen suddenly when a certain event or a stroke of fate turns a person’s life completely upside down. When you fall head over heels in love; or when, totally unexpectedly, someone breaks up with you; or when you’re involved in an accident or cause one; or when you test positive for something you’d rather not; or other such instances. When such things transpire, you have to quickly adapt your personal demands and expectations to the new circumstances, something accompanied by the paradoxical effect, already noted above, that you’re still thinking of what life was like before the dramatic event took place and at the same time you can no longer even imagine it.

Here again the individual shifts take place gradually and do so more often, i.e., it takes a whole series of individual events for the normal 0 to become a 1. This is the case, for example, in a romantic relationship when the initial phase of infatuation has ended and you begin to get annoyed by the other person’s habits and some of their personality traits, many of which you didn’t notice before. Or whereas in the beginning all you cared about was being together all of the time, more and more you’re finding such constant companionship a real constraint. The complete fusion and sense of security that you wanted in the first phase has now turned to an equally strong desire for more freedom. Or when someone breaks up with you, you go through an initial stage of shock and then various stages of grief. Denial and not wanting to admit that it even took place turns into outright anger; this, in turn, gives way to the genuine processing of this loss; from there emerges, hopefully, the search for a new way of being in the world and a new sense of self. Or when frustrated with being single, you start to treat yourself to one more tiny little gummy bear every day—it helps you get through the day. This new habit doesn’t show up on the bathroom scale for a long time. Then one morning you realize that you can’t zip up your jeans. It’s then that you’ve got to admit that you would rather change your entire wardrobe than go without that beloved daily hit of chewy, sweet pleasure from the package with the cheerful yellow bear on the cover. One moment of indulgence or of stress eating has turned into dependency.

In Infinite Jest, subtle shifts like these are fundamental, which also explains the huge difference between the narrative time (i.e., the time it takes to read through the book) and the narrated time of the novel. The main plot, which spans 1000 pages (including footnotes), covers a period of just three weeks. It takes time to describe all the little details and individual events that are relevant for observing the main protagonists’ shifting internal reference points. There’s the upward trajectory of the aspiring tennis pros at E.T.A., their arduous, daily struggle to meet their own expectations and those of their coaches by at least defending their current ranking and, if possible, by reaching the next higher “plateau.” Then there’s the ongoing downward descent into substance-related addiction or clinical depression, which often go hand in hand. Ennet House residents have already experienced this downward spiral to hit existential rock bottom, at least once in their lives. For the most part, they’re now on a cautious upward trajectory, where the first priority is to get through each day without being swallowed up by their inner black hole and craving for their substance of choice.

The Gift of Total Focus

The parallels between professional sports and addiction in Infinite Jest are hardly arbitrary. DFW chose them quite deliberately. Both are ultimately about the same thing: total and uncompromising devotion to a cause. By the time someone reaches a place of utter devotion, however, a multitude of smaller and larger reference point shifts have already taken place. You start off on such a path quite innocently, out of boredom and/or curiosity, and then you realize that you have a certain basic inclination towards the sport or your preferred substance; the first experiences of success and/or exhilaration occur, which you desperately want to repeat; your environment offers affirmation, encouraging you to continue, either because you are talented and can thus stand out, or because you don’t seem to have a particular talent for anything else and thus you simply let yourself drift along down the path that you are headed down. The experiences of exhilaration increase in intensity and frequency, as do the negative feelings of defeat and depression, which you try to compensate for by training or consuming a bit more, then a bit more, until finally you’re devoting almost all of your time and energy to the sport or to the substance.

Your initial naiveté is now over, replaced by growing pressure, both internal (raise the level of your performance, raise the intensity, etc.) and external (satisfy coaches and the audience, serve various creditors, etc.). Inevitably, a halfway normal social life falls by the wayside. You’ve got to focus; the interplay of immeasurable pressure, self-doubt and feelings of loneliness, on the one hand, and completely uninhibited intoxication and self-exaltation, on the other, pushes you to lose your balance; the distances between the two extremes become increasingly smaller.

The parallels between professional sports and addiction end here, for the time being at least, because while the aspiring professionals are supposedly heading further and further upwards, exceeding their physical limitations, the addicts’ path leads steadily and dramatically downwards, to the brink of death. The parallels resume, however, when the addicts have overcome their mental-physical and social-human low point, and then begin to slowly pick themselves up again and try to transform the energy that has been released from their former total devotion into something less destructive. The previously untamed energy must now be artificially channeled. The days in the rehab clinic are thus marked by strict procedures and rituals, which, in turn, are not unlike the daily structure of a sports training facility. Once again, it’s a matter of being purely fixated on one thing—only this time not out of desire, but out of (self) compulsion. Staying on the ball (metaphorically and literally), come what may, day in and day out; not thinking, not looking to the left and right, but simply carrying on, even if you’re tired of it all, feel infinitely tired and/or your “bones are ringing, the way that sometimes people say that their ears are ringing” (INFJ: 100). One day at a time. After the match is before the match.

There’s at least one decisive difference between professional sports and addiction; it’s less related to social prestige or ambition or self-discipline than you might expect and more related to the degree of suffering. Just to be able to wake up every day and start all over again, aspiring professional athletes have to be able to suppress the extent of their suffering—the mental and physical torment to which they have to expose themselves during their long, repetitive daily training sessions. Otherwise, they wouldn’t stand a chance at increasing their own performance level and holding their own against the competition. In this regard, addicts differ from athletes. This ability to suppress the extent of their suffering is their absolute undoing—regardless of whether they are in the active phase of addiction or in one of withdrawal and abstinence.

You might think that even when in the active phase of addiction, the mere memory of the psychological and physical pain that they suffer every time they come down would itself be enough to inspire the addict to keep their hands off their drug of choice when the opportunity to use it came along. However, that very mental and physical pain is so present and all-encompassing that there seems to be only one way out of the agony: the next dose. The stronger the pain, the higher the dose, the stronger the pain, the… What’s important to keep in mind is the fact that it’s a gradual process. Following the discussion of fish and water, there’s another (better known) metaphor that has to do with vertebrates and water: The addicts are comparable to frogs that sit in their own respective pots and don’t notice how the water around them slowly heats up to a life-threatening boil. A frog from outside the pot, who jumps in when it’s already boiling, would immediately jump out; it did not experience the shift from 0-1 gradually and thus immediately notices the danger it poses to its life.

After withdrawal, the addicts themselves look incredulously into the pot of boiling water from which they were able to free themselves just in the nick of time. In this phase, they’re dependent on permanently visualizing the suffering that accompanies the active phase of addiction, in all its unbearable aspects. This is meant to help them stay clean despite all of the strains and stresses that abstinence entails. At first, this works pretty well, because the memory of what it feels like to sit in water that’s far too hot is still strong. Gradually, however, the memory fades and the addict’s feeling of absolute despair gives way to a feeling of relative stability, accompanied by increasingly minor concessions, which culminate in an overestimation of themselves. From there, it’s only a small leap back into the pot of hot water. The inner void, the inner black hole, which their substance of choice was mostly able to cover up for so long, then creeps back until the suffering brought on by abstinence exceeds the suffering from active addiction, and once again there seems to be only one way out for the addict: the next dose.

As discussed above, what’s essential to bear in mind about the reference point is that it tends to shift slowly, gradually, largely undetected, further and further away from a fixed base. In the case of addicts that means moving ever further away from the misery that accompanies the active addiction (or the memory of it). So here, too, a bubble is formed that has a devastating impact on those affected and on their environment. At some point, the bubble bursts and after bursting, it more-or-less quickly re-forms, only to burst and form again, and burst and form again, and so on and so forth. To break the vicious cycle and disrupt it in a lasting way, it’s not enough to put a pot of boiling water in front of the addicts every day, i.e., to appeal to their reason or memory. The substance has an overpowering attraction and effect that supercedes all reason, and therefore its counterpart, abstinence, must also be elevated in significance.

In Infinite Jest, the AA meetings thus resemble religious or spiritual revival meetings, in which the participants are sworn to the “Gift of Desperation”, which enables them to defy “the Disease” (or “the Spider”) by resisting the overpowering desire every single day (“One Day at a Time”) and continuing to come to the meetings (“Keep Coming”). They swear to put themselves in the other participants’ shoes (“Identifying”) and to avoid falling prey to the mistaken belief that they’re the great “one in a million” exception and don’t belong there or can somehow manage to stay away from the pot of hot water permanently without constant support from the outside. Only by identifying with the other members of the group, and their personal stories of their downward slide, are the former addicts able to receive and pass along the sacred message (“Carrying the Message”).

In short, this message is simply “Keep Coming” or “Keep Coming to the Meetings.” It’s a circular argument that initially drives some of the Ennet House residents to despair, because they hope for some kind of redemption and meaning and instead have to realize, whether they want to or not, that the only meaning is to stop looking for a fixed meaning. But as long as they focus on the carrot—across which is written KEEP COMING—that’s dangling in front of their noses, and as long as they don’t look to the left or to the right, don’t analyze anything, then, according to AA philosophy, they have a realistic chance of staying on the right path.

You Can’t Have Your Carrot and Eat It

The dangling carrot metaphor appears a number of times in Infinite Jest, especially at E.T.A. Here the carrot stands for the next “plateau,” the next higher-ranking position that the tennis kids should focus on reaching without being distracted by any influences or temptations from the outside world. Younger tennis kids in particular make the mistake of hanging the carrot far too high at the outset and chasing the idea of a great tennis career, which for them is the epitome of fulfillment and even redemption. The coach’s task is thus to lower the carrot, bit by bit, so that the message KEEP HITTING THE GODDAMN BALL becomes clearly visible. In this, they’re unconsciously supported by the in-house E.T.A. guru, Lyle, whom the desperate tennis kids seek out in the weight room and ask for advice and who explains to them with the patience of a saint that even the ultimate carrot, the achievement of “the Show,” would by no means bring any sort of redemption. Because just like the carrots that dangle metaphorically in front of your nose, you can’t ever really reach the ultimate achievement. As soon as you think you’ve “caught” the carrot, it actually moves a little bit further away or is replaced by a new one. And so, even if you do achieve fame and prestige, then you have to deal with the fear that you’ll lose that very fame and prestige and with the need you now have for privacy and a sense of normalcy.

This principle of the dangling carrot also accounts for capitalism’s success and appeal. As has already been shown above, consumption is not about the complete satisfaction of a need, but about the constant creation of new ones. Capitalism suggests that a certain need could be satisfied by the purchase of a certain product, but immediately after consumption takes place a new need is formed, which, in turn, has to be satisfied by yet another product. Behind this, there also lies a promise of redemption, the idea that you might be able to escape your inner void, the black hole, if you consume this or that product or experience. Upon closer inspection, though, you see that the capitalist carrot says nothing other than: KEEP CONSUMING. A circular logic works here too, so long as the consumers stay focused on the carrot and don’t look to the left or to the right.

Capitalism’s target has changed quite a bit in recent decades, however. Capitalism is no longer so much about selling a particular product as it is about marketing a particular activity. And the activity is targeted at a particular resource: the consumers themselves. As can be seen in the more than lucrative mindfulness/self-help/happiness industry, this resource is infinitely reproducible, so long as care is taken to ensure that the reference point shift from 0 = “dissatisfied/suboptimal” to 1 = “satisfied/optimal” never ceases, or that one shift immediately leads to the next one. The wide-ranging market of self-improvement thrives on the fact that the promised end state is never reached and instead the feeling is maintained among consumers that they are still a little bit inadequate, insufficient or not happy enough. There’s simply always something to optimize, be it eating habits, attitudes towards life or the authenticity discussed above. And so, for example, it’s also possible to earn incredible sums of money with minimalism and renunciation. After all, there’s always a coach or an app available to help you figure out how to do it right by quitting something, sorting through your stuff, and scaling down.

But apart from this self-replicating mechanism of action, it’s always astonishing how many individuals invest a considerable amount of their time and money in various self-help programs and strategies and thus ultimately in mantras that—let’s be honest—don’t differ significantly from the mantras espoused by AA veterans in Infinite Jest. Both traffic in banality and clichés. One theory that could be used to explain this phenomenon is that despair/loneliness/and the-need-for-direction-of-some-sort in our contemporary society has taken on such a serious dimension that many feel the need to cling to simple truths and promises of potential meaning. Another theory is simply that the distress you may feel is a deeply personal issue. Figuratively speaking, you don’t necessarily have to be sitting in a pot of boiling water to feel overwhelmed and something like despair. What already feels like 185-degree hot water to person A, may not even inspire person B to withdraw their hand from the pot, because they’ve lost a normal relationship to water temperature or never even had one to begin with. I think it’s safe to say that there’s some truth to both theories. There’s not enough space here to go into the first theory, though. So for the conclusion we’ll stick with the second one.

86,400 To The Infinitieth

If you take for granted that the carrot pretty much stands for some sort of aspiration that you’re working towards and around which you’ve been orienting yourself and waggling along, making it possible for you to get through your—at best unsexy, at worst unbearable—everyday life, then the crucial question is: “How high do you hang the carrot within your personal default setting? From which “plateau,” or from which zero, do you even begin to try and grab at it? In Infinite Jest, the answer to this question is, as you’d expect, rather extreme, since most of the protagonists don’t really have a healthy relationship to changing “water temperatures:”

You’ve got the talented 17-year-old, Hal, to whom all of the doors seem to be open. The fact that he was able to work his way up, plateau-by-plateau, to second place in the internal E.T.A. rankings—behind the Canadian John (“No Relation”) Wayne—is due in no small part to his secret consultations with “Bob Hope.” For a long time, the prospect of getting high every day in the E.T.A. basement helped him keep up his fighting spirit and will to go on. However, when someone accuses him of taking drugs of some sort, he has to quit temporarily in anticipation of a drug test, forcing him to, as he puts it (or rather his more experienced friend, Mike Pemulis does), “Abandon All Hope” (INFJ: 1064, fn 321). Without the daily high, he’s utterly defenseless against his emotional void and even loses his desire to play tennis or do anything at all. In this state, he lies down on the floor of Video Room 5, focusing on breathing in and out. Rejecting the question of how he might get up again as too complicated, he thus simply lies there, inhaling and exhaling.

Katherine (“Kate”) Gompert would gladly trade Hal’s condition for hers. Gompert suffers from psychotic depression, a severe form of depression that she describes as an unbearable feeling, as if every single one of her body and brain cells were afflicted with severe nausea and wanted to throw up—all the time, non-stop. Like Hal, for a long time, she’s only able to make it through the day by looking forward to her daily high, which helps to alleviate, albeit briefly, her unbearable anguish. But for the time being, even that carrot’s gone, when after her latest suicide attempt, she ends up in a psychiatric ward and then Ennet House, where, like everyone else, she has to stay clean. Then, the only thing she can focus on is the hope that the next moment will be bearable enough to prevent her from jumping out the window in a state of utter despair. She can always fall back on the example of a former, fellow psychiatric patient, Mr. Earnest Feaster. When they met, the devout Feaster had already been suffering from psychotic depression for an unimaginable 17 years, during which he’d never seriously contemplated suicide. He’d longed instead for death in life, a state of complete psychic numbness and unconsciousness that he eventually tried to achieve with the help of radical psychosurgery. Gompert never dared to inquire further. But it can be assumed that after he had his entire limbic system removed, there were no longer carrots of any sort dangling before him.

Tony (“Poor Tony”) Krause, a transgender junkie from Boston’s underworld, also craved complete unconsciousness. Krause loses his connection to his crowd through a chain of, shall we say, “unfavorable” personal crises. The upshot is that he loses access to heroin as well as to a safe house and, at some point, to a cough-syrup concoction that was supposed to take the place of the heroin. Only, unfortunately, Tony never loses consciousness. Not when he, against his will, goes cold turkey in an empty dumpster, nor when he moves from the dumpster to a public library restroom in order to deposit the various bodily fluids coming out of his body. And when he finally pulls together whatever strength remains to his now 100-lb body to visit his “plan C” dealers, he suffers an epileptic seizure in the subway on the way. Even then, his consciousness doesn’t do him the favor of finally opting out. In all these phases Poor Tony Krause has no choice but to cling to the only carrot left to him: the hope that the next second will pass more quickly than the last one and won’t be “carried by a procession of ants” (INFJ: 302).

Don Gately is all too familiar with such circumstances. In the early stages of his withdrawal, he felt “the sharp edge of every second that went by” during the day and was haunted by “freakshow dreams” (INFJ: 280) of the worst kind. After rehab, for the first time in his life, Gately finds himself on a slightly better path. Unlike some of the other protagonists, complete abstinence has had a consistently positive impact on his ability to interact socially; people like to talk and connect with him. You could say that he’s the “soul” of Ennet House, where, as the newly appointed head chef, he sets out to fulfil his fellow residents’ culinary needs by serving up a satisfying meal, every night. Gately is amazed to discover that the mantras espoused by the AA sponsors actually work and that he somehow pulls off remaining clean, every day. But when a life-threatening gunshot wound puts him in the hospital he’s confronted with the opportunity to take his drug of choice, the powerful painkiller, Demerol®. Fevered, in pain, and unable to speak, he tries to resist the doctor-recommended sedation with all the strength he has left, but this means alternating between unimaginably intense pain and flashback-like nightmares. In this state of semi-consciousness, Gately finds himself, once again, forced to transform the omnipresent AA mantra “One Day at a Time” into “One Second at a Time.”

What these four protagonists have in common is that they’re trapped within their own “locked-in-state,” that is, somehow imprisoned in a fully conscious state, within themselves and time. Even in their addicted state, they were prisoners of their own toxic thoughts, 99 percent of which revolved around themselves. Intoxication provided them with a chance to momentarily escape their heads, bodies, and time. And so, it’s only reasonable to expect that when they cease to take their preferred substance, the suffering does not disappear at all. The opposite holds true. There’s always extreme phases, when it’s no longer enough to muddle your way through the day-to-day, when to merely survive you have to count the seconds—and those seconds can last an eternity.

It’s precisely these small, nearly hidden, linguistically virtuosic snapshots that make Infinite Jest so unique. The novel is undeniably a work of universal merit that can be viewed from multiple perspectives; it’s overflowing, overtaxing, overstated. Sure. But it’s also more than worth the time required to read it, if only for the playful way it deals with time and the individual’s perception of time. You have to find the courage to confront the possible intense suffering that sticking with it entails. Very few novels manage to make the reader (most likely one of those beleaguered postmodern individuals referred to above) so very aware of their own current default setting in the way that Infinite Jest does. It may even coax such a reader or postmodern individual out of their rabbit holes of self-improvement, pushing them to broaden their view a bit. If nothing else, your normal-0 comes off looking a lot better when compared to the lots of Gompert, Krause & Co.

– V –

For the conclusion, I’ve reserved an additional five essential insights from Infinite Jest, which you may consider my humble contribution to the self-help industry.

First, mantras help, not despite the fact but because they’re so terribly banal and clichéd. In a way, they represent time that’s been compressed, a condensed version of millions and millions of collected individual experiences taken from (post-)modern society. That’s exactly why they act almost like a pill with a neutralizing effect, one that staunches the tide of complexity flowing out of your head into the outside world. And when the inner black hole threatens to swallow you up on a Tuesday afternoon, they may well be the only thing to which you can still cling.

Second, living by the mottos “be true to yourself” or “live in the moment” can be a damn lonely business. Authenticity is not for cowards.

Third, the day consists of 24 x 602 seconds, into which you can fit a bajillion different, potentially shitty emotions and thoughts. And, unlike footnotes, sadly, you can’t skip a single one of them. Good resolutions? Fine. But if said black hole threatens to swallow you up on a said Tuesday afternoon, then unfortunately you have to go through it all alone and are then returned to the prison of your own body and mind.

Fourth, in and of itself, no second is completely unbearable.

Fifth, life is an endless interplay of zeroes and ones. Easy come, easy go. You can never reach the carrot. That’s ok so long as you can still somehow see a kind of carrot dangling in front of your nose and it hasn’t long since landed chopped up in the Stolichnaya®.

David Foster Wallace lived for almost 1.5 billion seconds. In his incredibly complex literary oeuvre, he examined, among other things, his own struggles with severe depression and addiction. Aware of this, you may ask yourself: How many of his 1.5 billion seconds on earth were devoted to annihilating a seemingly infinite number of dark thoughts and ideas? How many stretched far beyond what a person can be expected to endure? It’s impossible to know. While medication may have helped him blunt the edges or mitigate his depression, it was nonetheless a weight he had to carry throughout his life. In the end, the carrot that had dangled before him, the one that had helped him carry on, was hanging too high.

Source Directory

- Coen, N. (1998). The Big Lebowski [DVD], London/Los Angeles: Working Title Films Ltd.

- [ASUPFTH] Foster Wallace, D. (2018). A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again. In The David Foster Wallace Reader (1st ed., pp. 763–844). London: Penguin.

- [INFJ] Foster Wallace, D. (2006). Infinite Jest (10th anniversary ed.). New York: Back Bay Books.

- [TISWA] Foster Wallace, D. (2005, May 21). This Is Water. Transcription of the 2005 Kenyon Commencement Address – May 21, 2005. Purdue Universitiy, Indiana. Retrieved January 17, 2021, from https://web.ics.purdue.edu/~drkelly/DFWKenyonAddress2005.pdf

- Gilbert, M. (2012). The “Infinite Story” Cult Hero behind the 1,079-Page Novel Rides the Hype He Skewered. In D. Eggers (Ed.), Conversations With David Foster Wallace (1st ed., pp. 76–81). Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

- Miller, L. (2012). The Salon Interview: David Foster Wallace. In D. Eggers (Ed.), Conversations With David Foster Wallace (1st ed., pp. 58–65). Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

- LeGuin, U. K. (2019). The Dispossessed (1st edition). London: Orion Publishing Co.